Dining in the Georgian Era: à la française

- Paullett Golden

- Dec 20, 2023

- 24 min read

Updated: Jun 15, 2025

Publication Date: Dec 20, 2023

“What a superbly featured room and what excellent potatoes!”

When it comes to dinner parties, are you familiar with the difference between dinner served à la française versus dinner served à la russe? How about which our heroes and heroines would experience while attending those all important dinner parties of the Georgian era? Let the research be served!

Brief Overview

The French style (à la française) was in use from the 16th century on into the late 19th century. Around 1860, the Russian style (à la russe) became popular. Which means, we've just answered the question of which our heroes and heroines would have experienced. The fine dining experience we are most familiar with in modern society is the Russian style. There are differences to how we dine now, of course, especially if we're eating at home versus at a restaurant, but our modern fine dining experience is based on the à la russe rather than what our heroes and heroines would have experienced at the dining table. We'll breakdown both styles, from the tablescape to the dishes and the role of the footmen, but our main focus will be on à la française.

à la française

French style, or à la française, is when all items of a course are served on the table at the same time. The table is arranged artistically, with a symmetrical pattern of dish shapes to ensure the top and bottom of the table match, the sides match, and even the corner dishes all match in size and shape. The tablescape is the food, as there are no decorative centerpieces, vases, or otherwise, just the food, the dishes serving as the decoration. The meat dishes were placed in the center with the accompaniments on the sides of the table. At each end, near the host and hostess were the soup and fish (ie the "removes" for the meal, but we'll get to that in more detail soon).

When the butler steps into the drawing room to announce dinner is served, and the guests proceed into the dining room, they are greeted by a ready table--the entire first course already on display for the guests to feast on with hungry eyes.

Typically, the first course was soup, fish, and meats. The second was roasts and baked dishes. To begin, the hostess and host would serve the soup and fish for the first course. If no fish, then the host would serve the soup. If fish, then the hostess would serve the soup while the host filleted the fish. While you might consider the soup and fish as the "appetizer," there wasn't an appetizer, as such, merely the first course, and the soup and fish--called "removes," which we'll get into shortly--would be eaten first before diving into the meat. It was the soup and fish of the first meal that the hostess and host kept at the top and bottom of the table and served to their guests as that symbolic gesture of generosity, while the guests could serve themselves from the meat platters. For the second course, the host and hostess would again do the serving, this time from the roasts--which were served whole and intact. Once the roasts were carved and served, the guests could choose whatever else they wanted from the cooked dishes on display during that second course.

However crude of a description, you could say the French style was basically a buffet in two to three courses, but rather than heading to the sideboard or buffet line, all of the food was on the table, never requiring the guests to leave their seats. Since the items were on display, the guests could customize their plates however they wished by adding whichever sauces and however much sauce they wished, whichever combination of dishes they wished, etc. It was all to the taste of the guest, not the cook.

A few points on etiquette here:

Whichever gentleman sat next to a lady at the table, he would offer to plate the food for her so she would not be reaching here and there to grab food. Granted, she could, but it was the polite thing to do for the gentleman next to her to offer to do so on her behalf.

No one reached over anyone else, rather whoever had a dish before him would offer to plate from that dish for those around him after he had plated his share--the dish itself was never moved.

It was not well mannered to go for seconds or thirds or even take multiple items from various dishes--the expectation was to take shares between the nearest two or three dishes and be contented with that lot.

If there was a dish across the table you desired, you could have a footman or a guest take your plate and add from that dish to the plate for you, but it was not well mannered to do so. A good host would always provide ample selections within reach of each guest to avoid this. The guest would do well to choose their seat next to the dishes they desired most. Since the placement of dishes was fairly standard, it shouldn't come as much of a surprise where the best seats were for certain items, but really, a guest should be contented with his lot, regardless his seat.

Given the first point of etiquette and the previous point, one might discern that having your favorite dish was not always easy. Jane Austen even remarked in a letter that despite her having asked several times, the gentleman nearest the mutton never would offer it to her. Read more about that little tidbit in Eileen Sutherland's article "Dining at the Great House: Food and Drink in the Time of Jane Austen."

There were not waiters/footmen removing one plate in exchange for another to serve the next course as we have today. It was poor etiquette for a footman to disturb the guests or the dishes. Their primary purpose was to refill drinking glasses. Beverages, be they wine or otherwise, were available at the sideboard in the dining room, within easy reach for the footmen to refill glasses as needed. All refills were not done at table, rather the glass was taken to the sideboard to be refilled, and then returned to the guest. This avoided spills and disturbing the guests.

When the table is first arranged, there are two tablecloths adorning the bare wood, and then the platters are arranged in a specific scheme for display and convenience of guests. Once a course was completed, the footmen would remove all dishes from the table, all plates, and all cutlery, and finally the top tablecloth, revealing beneath it the ready undercloth, upon which they would then lay out new plates, cutlery, and the platters of the next course--yes, while the guests are still seated at the table. Typically, the "removes" would be placed first to provide a conversation piece and also time to carve/serve while the main dishes of the next course were being added. If there was a dessert course, the undercloth would be removed, and the guests would enjoy dessert over the polished, bare wood of the table.

A fantastic little post on the history and etiquette can be found from Peter Hertzmann e-zine à la carte.

Before we look at à la russe, let's dig into the details of each course for à la française. Hang on to your cutlery.

Courses à la française

Generally speaking, our heroes and heroines would have expected two courses during their dinner experience. Within each of those courses, they would have between five and twenty-five dishes to choose from. The general lay of the land is soup and/or fish as the removes, with the meat dishes as the main items, and finally the cooked dishes. The roasts can be offered as a remove of the first course or of the second course (more on this later). Popular roast choices were venison, fowl, peacock, hares and rabbits, Calf's heads, tongues, turkey, and ham.

A typical at home dinner with family would consist of two courses of five to twelve dishes per course and two removes.

A typical dinner party intending to impress its guests would consist of three courses of six to twenty-five dishes per course and several removes. The third course on these occasions would be dessert.

How to determine the number of dishes on the table? A rule of thumb is to offer the number of dishes equal to the number of guests. Each course should have the same number of dishes. If one were to host an important banquet, it would not be uncommon to see as many as seventy dishes for the combined efforts of three courses. Royal banquets were known to exceed this vulgarly, such as having seventy dishes per course.

First Course

The first course always began with soup and/or fish served directly by the host/hostess, plus the meats. The first course was not an appetizer rather the main meal. One could, essentially, fill up on the first course alone. Think of it like this--Meat first course, Carbs second course. While usually soup and fish were served--although the hosts could decide to serve only one if they wished or have one as the remove of the other--it was polite for a guest to choose one or the other, not both. Choosing one's seat was wise, for any meats requiring carving would need to be done so by the gentleman nearest that dish.

Second Course

The second course was what they called "Made Dishes," which were essentially the baked/cooked dishes, such as roasts and casseroles, and consisted of things like ragouts, hashes, pies, fricassees, veal, plum pudding, fritters, etc. If the hostess chose to include vegetables or salads, they would be part of the second course. Roasts included birds and meat roulades, typically, the more exotic the bird, the wealthier the family.

Removes

This is not a course rather it is an element of each course. The "removes" are the items in each course that are placed at the top and bottom of the dining table, intended to be removed/replaced once finished. The host/hostess serve the removes to the guests, while all other platters are a serve-yourself style. The "removes" were the soup and fish in the first course, which were then replaced by the roasts. The only items in a course that would be removed/replaced before the end of the course were these removes, all other items remaining on the table so the guests could have their fill with ample choices of what to sample and eat.

An important point about "removes" so that there's not confusion should you look at menus and see discrepancies: Not every host/hostess chose to have removes, and if they did, what was considered a remove was entirely at their discretion. Aside from soup and fish, the roasts were the most common choice to be served as a remove. And thus, in some menus, you might spot the roasts in the first course as being the removes of the soup and fish--so, once the soup and fish has been served, the host can then offer roast as one of the meat options. But in other menus, you might not spot the roast until the second course. One of the most common I've seen is roast being served as the first remove of the second course in order to provide a talking point for the guests and bide carving time while the footmen prepare the table with the second course of the baked foods.

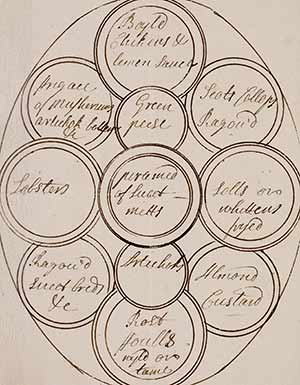

Image to the left: Foldout engraving of table layout for an elegant second course, from Elizabeth Raffald's The Experienced English Housekeeper, 4th Edition, 1775. Image to the right: Table plan for a supper at Saltoun Hall, by permission of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, [MSS.17853, f.3], retrieved from National Library of Scotland

Dessert

Here we have an interesting third course, as what our heroes and heroines would have seen in the 18th century was different from what they would have seen in the Regency, splitting the Georgian era by way of dessert.

Let's look at the Regency first, and then backtrack to the 18th century.

The final course in the Regency, if offered, was something light and refreshing. This was almost always finger-foods, not something requiring cutlery. Our heroes and heroines would not have seen sugary confections, rather they would have been choosing among fruit, cheese, syllabub, jellies, ice creams and ices, and nuts. On special occasions or particularly large dinner parties, especially if the hostess wished to impress, there might be a sponge cake, blancmange, or sweet gelatin included, but usually dessert was variations of fruits and creams.

The use of a sweet, ie sugary, dessert was an Americanization of the French style, one remarked on at length by British travelers who were perplexed by the heaviness and sugar-laden confections. Our British heroes and heroines would not have seen decadent and sugar-coated confections at the table, rather the dessert would have been in keeping with nuts, raisins, fruit, syllabub, and ices.

It was not uncommon for the dessert course to be skipped altogether in favor of exclusively savory dishes for those first two courses, followed by tea in the drawing room. The most common service our heroes and heroines would have seen would be two courses--soup and fish and meat, and then the baked dishes--followed by their return to the drawing room for tea. Only at an especially large dinner party would there have been a dessert course, but even then, its intention was to cleanse the palate from the savory dishes before having after-dinner tea, and thus the popularity of ices, fruit, and nuts.

That said, the desserts of the 18th century were quite different. Dessert was an important and extravagant feature of the early Georgian era, especially during the middle years, say around 1750s. The desserts were elaborate, typically shaped to resemble familiar architecture or to showcase a scene from mythology or a pastoral setting. While sugar could be used, the desserts were usually made from fruits, jellies, sweetmeats, and creams. It was the display that was decadent, not the dessert itself, if that makes sense. Interestingly, not all of the desserts would even be eaten, as some hosts preferred to make it a display only to show off the skills of their confectioner. Wealthy households employed confectioners for this purpose. The dessert sculptures could be quite elaborate, such as a recreation of one's own estate gardens in detail. Don't imagine a multitiered sugary cake, here, rather imagine porcelain and glass used for the structural build, and then fruits and sweetmeats adorning it to provide the color and detail. A not to be missed article is from Jane Austen’s World: “18th Century Dining: Elaborate Dessert Table Centerpieces for the Fabulously Wealthy.”

It's interesting that desserts changed by the Regency, especially when by the mid-19th century, we would see a resurgence of the elaborate dessert centerpieces, as I'll mention in the Russian style to come.

I'll save the menu items for the end. For now, before diving into the à la russe dining style, I recommend perusing this fantastic article from Eileen Sutherland in Jane Austen Society of North America's twelfth edition of Persuasions, “Dining at the Great House: Food and Drink in the Time of Jane Austen,” as it offers details about both menu items and the changing role of the dining room throughout the Georgian era.

à la russe

Russian style, or à la russe, was promoted from about 1860 onward. This was pushed mostly towards the merchant class and lower gentry at first and involved small, individual plates, one at a time, much as we have today. One of the main differences between then and now with this style is that we use the Russian style but usually with only three courses, whereas at the time, they would have between eight and fourteen separate plates, one after the other. The service itself, from the platting and tablescape to the role of the waiter/footmen is all in keeping with how we typically eat today, and not at all what our heroes and heroines would have experienced.

The waiter/footman was an integral part of this service. They would bring an artfully arranged platter into the dining room, the platter containing the available dish and adornments for that course, and one guest at a time, the footmen would present the platter for the guests to take from it what they wanted. As another variation of this theme, at the host's request, the waiters/footman could serve each guest an individual plate for each dish/course rather than a platter of choices, which would allow everyone to start the meal at the same time rather than waiting for the platters to make their way around the table.

Since the food was crafted and platted in the kitchen rather than at the discretion of the guests, the dishes would arrive already sauced and seasoned. This did, of course, reduce a guest's choices and ability to customize their dish. Would you rather have the duck than the hare? Tough. Don't want the sauce? Tough. The good part was that each dish would be served hot, whereas with the French style, by the time the guests had worked through their soup and fish then platted their choice of meats, the meat dishes would have been sitting on the table for half an hour or longer.

No food was displayed on the table, rather the table was adorned with decorative centerpieces, usually of flowers and fruit, and sometimes of the dessert to come, which would have been a masterpiece creation, such as a recreation of the estate itself.

Could our heroes and heroines have encountered the Russian style prior to 1860? Possibly, but not likely, not unless they (or their host) were exceptionally well traveled. If they happened to have been in Paris around 1810, which is when/where a Russian Ambassador introduced this style, then they could have experienced it but likely wouldn't have brought it back to England. If they had traveled to Russia or some variation of that theme around the early 19th century, they certainly would have experienced it, but again, likely wouldn't have brought the style back with them for their English guests. However possible, it's unlikely our heroes and heroines would have seen this style prior to the 1860s. Interestingly, although it is the Russian style, it is often considered just as French in origin as the French style since the first place the British encountered it was in Paris or from those who had visited Paris.

Additional Dining Tid Bits

For grins and giggles and not necessarily to do with either type of service, I thought I'd add a few fun facts.

Napkins were not usually used until late Regency, although some households may have used them despite their waning popularity. They were used in the earlier part of the 18th century, but they went out of fashion by late 18th century and into the Regency, not making a return until late Regency. To dab their mouths (never wipe), they would use the edge of the tablecloth, which was quite long. Rumor has it this was in direct opposition to the French and more of a show of solidarity against the French than anything else, as the French used napkins at the dinner table--can't very well be like the French when at war with them. Ironic since they were dining à la française. This is one of those fun facts that we typically don't see in our hist roms since it's a case of "Do I stick with accuracy, or do I make the scene more relatable?" Having our heroes and heroines dabbing their mouths with the tablecloth might give a reader/author pause, and so napkins are often included in novel scenes. Since there was not a "rule," and since some households may have preferred napkins over politics, it's not inaccurate to feature them.

Dinner was served early in the day as the main, hearty meal. This was typically geared either for the working class who needed sustenance to make it through the rest of the day ("lunch" was not a thing yet except for travelers who stopped at inns to rest their horses, in which case they could have a luncheon or nuncheon of cold meats) or for the entertainment of guests by the wealthy. For the working class, dinner and high tea were synonymous. For the gentry, dinner typically happened around three in the afternoon. The more common one was in social status, the earlier it took place in the day. The wealthier one was, the later it took place in the day. This was to do not only with schedules--work day versus evening entertainment, early wake up vs late to bed, etc.--but also the ability to light one's house after dark. Some of the wealthiest families would serve dinner after dark just to showcase their ability to light the dining room with candles.

Supper took place at the end of a day and was exclusively a family affair or reserved for the closest of friends, except for the case of balls, then it was the evening meal to sustain the guests, usually occurring around one in the morning. Supper at home consisted of cold meats and fruits. Supper at a ball was not dissimilar to what they would see at dinner, although it was considered supper rather than dinner or high tea because of the lateness of the evening.

There is often talk of seating arrangements in hist roms. This was at the discretion of the hostess, but typically dinner parties wouldn't have assigned seats, leaving guests to sit next to whomever they wished.

It was only polite to speak to the person to your left and/or right, never anyone across the table or past your immediate neighbors. That would not have applied to informal or family dinners unless the host/hostess was a stickler.

Following dinner, and after the gentlemen had finished their port and cigars to rejoin the ladies in the drawing room, tea would be served, usually accompanied by slices of bread and cake.

There were etiquette rules on the order of precedence, with whom you may speak at the table, and other considerations. This post from Regency History by Rachel Knowles covers quite a bit of this--not to be missed.

The number of servants in the dining room varied. For aristocratic dinners, the number of servants present typically was one per guest, except for when royalty was present, then it was two or more per guest. For less formal affairs and for gentry, there was usually one footman per four guests. It was not uncommon for an aristocrat to bring his own footman, especially if it were a less formal affair and he knew the dining room would be short on staff.

Menu Items

There are any number of cookbooks, bills of fare, and other resources that provide complete menus. Regional cookbooks from specific towns and villages are some of the best recipes, as they often contain dishes passed down through generations that may not have made it elsewhere in the country. There's no end to the popular dishes and recipes of the era! I highly recommend checking out Pen Vogler's books for menus, recipes, and dining facts. Check out Dinner with Jane Austen: Menus Inspired by Her Novels and Letters, as well as Dinner with Mr. Darcy: Recipes Inspired by the Novels and Letters of Jane Austen. Other gems by include Pen Vogler is Scoff: A History of Food and Class in Britain and Tea with Jane Austen.

That said, I think Daniel James Hanley's "Random Generation of 18th Century Feasts" is a fantastic resource to keep handy since it offers quite a few of the popular choices for each dish and course of a Georgian era menu. Rather than showing us what a hostess chose for her menu, this list allows us to devise our own menu. If you had between five and twenty-five dishes allowed for two courses, which items would you choose from his list?

His list of menu items is recreated here for convenience, but do note the original source, as this is directly from his post. I have made slight adjustments to be more applicable to our reading/writing needs (only because his original post included directions on rolling dice to choose items, which is great fun for gaming but perhaps not for our purposes here).

A Grand Dinner:

First Course:

Soups

Fish Entrées*

Poultry Entrées

Meat Entrées

The number of dishes on the table should be at least equal to the number of diners (up to 30).

Second Course:

Roasts and Main Dishes

Sauces served on the side.

Vegetables and Salads

For a total amount of dishes equal to the First Course.

Third Course (Entremets*):

Entremets equal to the total amount of dishes in the previous course. This stage is sometimes omitted.

Dessert:

Desserts equal to amount of dishes in previous courses.

*Note: “Entrée” was one of the dishes served at the beginning stage of a meal, and was secondary to the more impressive roasts and main dishes. An “Entremet” was a dish served between two other courses, generally after the roasts and before the actual desserts. The term encompassed egg and cheese dishes, as well as many sweet cakes and tarts.

An Evening Supper:

First Course:

Soups

Fish Entrées

Poultry Entrées

Meat Entrées

Second Course:

Vegetables and Salads

plus as many Entremets as needed to equal the total amount of dishes in the First Course.

Dessert:

Desserts

Soups

Almond Soup with Cream

Calf’s Head Soup

Capon Soup with Lettuce and Asparagus

Cock-a-leekie Soup – Scottish style soup of chicken and leeks.

Consommé of Beef

Consommé of Chicken

Crawfish Soup

Eel Soup

Mock Turtle Soup (veal)

Mulligatawny Soup (after 1780) – curried chicken soup

Onion Soup

Pea Soup

Pepper Pot – spicy meat stew from the Americas

Pigeon Bisque – with cream

Pureed Asparagus Soup

Pureed Carrot soup

Scotch Broth – lamb and barley

Soupe à la Reine (Queen’s Soup) – creamed chicken and meat broth with rich or barley

Squab Soup

Turtle Soup

Vegetable Soup

White Soup – made with veal and almonds

Meat Entrées

Beef Hachis – chopped beef with pickled cucumbers and onions

Beef Olives – thin steaks rolled around forcemeat, fried and served with mushroom suace

Beef Steaks with Oyster Sauce

Blanquette de Veau – white stew of veal with mushrooms

Boiled Sausages

Cabbages Stuffed with Forcemeat

Calf’s Brains Milanese – coated in breadcrumbs and fried

Calf’s Foot Fricasee – in white sauce, garnished with lemons and parsley

Calf’s Heart – stuffed with forcemeat

Calf’s Sweetbreads

Chicken Terrine – loaf of pressed, molded meat served cold

Civet de Lièvre (Jugged Hare) – hare cooked in a sealed earthenware dish, served with a sauce of its own blood and wine.

Fried Chicken Sausages

Fried Pork Sausages

Ham Pieces with Spinach

Lamb Chops with Brown Sauce5

Lamb Hachis – chopped lamb served in a brown sauce

Minced Veal – with lemon pickles and cream

Pâté de Foie Gras – molded paste of goose liver and truffles

Pork Terrine – loaf of pressed, molded meat served cold

Rabbit Pâté – rabbit meat reduced to a paste

Ragoût of Beef – stewed beef with carrots

Ragoût of Pig’s Ears and Feet – garnished with parsley

Roasted Hare with Bread Sauce

Salmagundi – English, composed salad of chicken, eggs, ham, and herring, garnished with capers and oysters

Veal Callops – thin slices served in white sauce

Veal Terrine – loaf of pressed, molded meat served cold

Venison Terrine – loaf of pressed, molded meat served cold

Fish Entrées

Baked Haddock with Butter and Bread Crumbs

Baked Salmon Stuffed With Oysters

Boiled Skate Served with Horseradish

Boiled Sole with Eggs

Broiled Mullet with Lemon

Cod Ragout, with Oyster Sauce

Crabs – dressed in butter and served on their shells

Crawfish in Aspic

Curried Lobster

Eels Stewed in Wine

Escargot with Garlic Butter

Filet of Sole with Mushrooms and Truffles

Fish in Aspic

Fried Eels

Fried Frog’s Legs

Fried Mackerel with Anchovy Sauce

Fried Scallops in Veal Sauce

Fried Smelts

Grenouilles à la Lyonnaise – frog’s legs with onions and parsley

Lobster* Fricassee

Lobster* meat with butter

Lobster* Paté

Mackarel à la Maitre d’Hotel – with herbed butter

Oyster Paté

Oyster Pie

Oysters on the Half Shell (seasonal)

Pickled Mackerel

Pickled Oysters

Pickled Smelts

Poached Cod’s Head

Pot Shrimp – pounded to a paste and formed into a loaf

Potted Salmon – pounded to a paste and pressed into a loaf

Salmon – cooked in paper with mushrooms

Salmon Steaks with Butter

Salt Cod with Egg Sauce

Smelts in Aspic

Stewed Cockles

Stewed Lampreys

Stewed Mussels

Stewed Oysters

Stewed Oysters in Cream

Turbot with Herb Sauce

Turtle Meat – shredded and served on its shell

Whole Poached Carp – with cucumbers arranged as scales

*When a scene is set in the American colonies (and the later United States), lobster would not be served at a formal dinner, as it was plentiful and cheap.

Poultry Entrées

Boiled Duck with Onion Sauce

Braised Ducklings

Chicken à l’Italienne – fried, with mushrooms, onions, ham & herbs

Chicken in Aspic

Chicken Pâté

Chickens Roasted on a Spit

Duck Galantine – boneless, stuffed with forcemeat, and coated in aspic

Filet of Chicken with Cucumbers

Jellied Partridge

Ortolans – songbirds fattened on grain, drowned in Armagnac, and roasted whole

Poularde Demi-Deuil – Chicken in white sauce with truffle

Pureed Pheasant

Quail with Mirepoix – onions, carrots and celery

Quenelles – chicken dumplings in cream sauce

Rabbit Cutlets

Sautéed Breast of Partridge

Sautéed Pheasant

Sliced Breast of Duck with Sour Orange Sauce

Sliced Grouse

Small Birds in Aspic – heads and feet left on

Thrushes on Bread with Cheese

Turkey Hachis – chopped turkey, with lemon and parsley

Roasts and Main Dishes

Beef Ribs

Boeuf à la Mode – larded beef braised and served in a sauce made form the braising liquid

Boiled Boar’s Head

Boiled Calf’s Head

Boiled Ham

Broiled Beef Steaks

Broiled Lamb Steaks

Calf’s Head à la Surprise – boned and stuffed with forcemeat and eggs

Fricandeau of Veal – veal larded and braised, glazed with a rich sauce

Glazed Breast of Veal on a Bed of Peas

Pike au Souvenir – stuffed with a forcemeat of various fishes and herbs

Pike Fricandeau – larded with bacon and served with a brown sauce

Pike in Court Bouilloin – served in a spiced wine and butter sauce

Pike with Lemon and Egg Sauce

Pike with Wine Sauce

Roasted Beef with Sweetbreads

Roasted Chicken with Truffles

Roasted Duck

Roasted Goose with Orange Sauce

Roasted Ham

Roasted Joint of Beef

Roast Joint of Venison

Roasted Leg of Lamb

Roasted Partridges with Bread Sauce

Roasted Pheasant with Bread Sauce

Roasted Squabs

Roasted Turkey with Oyster Sauce

Roasted Woodcock

Whole Roast Suckling Pig

Whole Roast Lamb

Whole Roasted Sturgeon

Whole Salmon – poached in wine

Sauces

Allemande – chicken stock thickened with a roux, with egg yolks and cream

Anglaise – thickened stock with egg yolks and anchovy butter

Béchamel – thickened cream sauce

Chasseur – brown sauce with mushrooms, shallots, and herbs

Devil – mustard sauce with stock, shallots and wine

English Bread Sauce – made with bread soaked in milk and melted butter, flavored with onion, pepper, and sweet spices

Espagnole – thickened brown sauce of beef and veal stock

Godard – demi-glace flavored with ham, champagne and mushrooms

Hollandaise – butter sauce thickened with egg yolks and flavored with lemon

Madeira Sauce

Mayonnaise (only after 1756)

Meat Gravy

Poivrade Sauce – thickened stock highly seasoned with pepper

Régence – thickened stock flavored with ham, onion, and wine

Rémoulade – mayonnaise with herbs and gherkins

Russian Sauce – thickened stock flavored with herbs, mustard, and lemon juice

Sarladaise Sauce – an emulsion of cream and egg yolks with chopped truffles

Sauce Robert – sauce of onions, demi-glace and mustard

Velouté – sauce of thickened veal or chicken stock

Verjuice – cream and egg-enriched chicken stock, thickened and made tart with grape juice

Vegetables and Salads

Asparagus – served on toast

Asparagus à la Polonaise – with parsley, chopped egg, and breadcrumbs

Boiled Artichoke – served with pots of melted butter

Braised Cabbage

Braised Endive

Braised Leeks

Broccoli in Butter

Buttered Cauliflower – on a bed of greens

Cabbage in Butter

Cauliflower in Cheese Sauce

Cauliflower in Cream Sauce

Cauliflower with Mayonnaise

Celery à la Crême – celery served in a cream sauce

Cos Lettuce Leaves

Cucumber Salad

Curly Chicory Salad

French Beans with Butter

Fried Battered Cardoons

Fried Celery

Jerusalem Artichokes in Cream Sauce

Mixed Field Greens

Peas in Butter

Peas with Butter and Mint

Pickled Cucumbers

Pickled French Beans

Pickled Green Almonds

Pickled Lemons

Pickled Mushrooms

Pickled Red Cabbage

Puree of Cauliflower

Puree of Parsnips

Puree of Potato

Puree of Turnips

Radish Salad

Red Cabbage with Chestnuts

Scalloped Potatoes

Steamed Purple Cauliflower

Stewed Cardoons

Stewed Mushrooms

Stewed Mixed Root Vegetables

Stewed Spinach

Entremets

Almond Cake

Apple Tart

Artichoke Bottoms with Whole Egg Yolks and Butter

Beef Roulade or Cold Beef Pie

Blancmange

Butter Cake

Cheese Tarts

Cherry Tart

Cheshire Cheese

Chicken Chaud-Froid – Chicken breasts covered with a jellied cream sauce, served cold

Cold Sliced Tongue

Edam Cheese

Eggs and Vegetables in Aspic

English Cheddar

English Flummery – thickened, sweetened starch set in a mold

Fondue

Fried Calf’s Liver

Fruit Cake

Gorgonzola Cheese

Gouda Cheese

Gruyere Cheese

Lemon Cakes

Macaroni Pie

Macaroni with Butter and Cheese

Mimolette Cheese

Mushrooms in Pastry

Neufchâtel Cheese

Omelette du Curé – with tuna, and carp roe

Omelette with Asparagus

Omelette with Cheese

Omelette with Chicken Liver

Omelette with Herbs

Omelette with Mushrooms

Omelette with Truffles

Orange Cakes

Parmesan Cheese

Poached Eggs on a Bed of Spinach

Poached Eggs on Toast

Pound Cake

Roquefort Cheese

Scrambled Eggs with Truffles

Stilton Cheese

Soufflé

Sponge Cake

Sweet Omelette (with fruit)

Toasted Bread with Slices of Ham

Veal and Ham Rissoles – fried croquettes served with white sauce

Venison Pie

Vol-au-Vents – puff pastries filled with chicken and mushrooms

Warm Brie

Welsh Rarebit

White Cake with Sugar Icing

Desserts

Apples

Apples in Pastry

Apricot Ice Cream

Apricots in Brandy

Butter Biscuits

Candied Almonds

Candied Cherries

Candied Chestnuts

Candied Violets

Cheesecake

Chocolate Creams – in individual glasses

Crème Anglaise (custard) – served in individual glasses

Crème Brûlée

Dried Figs

English Syllabubs – wine and sweetened cream mixed and left to separate, served in individual glasses that display the layers

Fairy Butter – egg yolks, butter and sugar flavored with orange flower water and put through a sieve

Fruit Ices in Various Flavors

Gooseberries

Île Flottante (Floating Island)– Mounds of flavored meringue in custard

Lemon Creams – in individual glasses

Macarons – biscuits of meringue and ground almonds

Madeleines – small sponge cakes baked in shell-shaped molds

Marzipan Fruits in Assorted Shapes

Mille-feuille – layers of crisp flat pastry alternating with layers of fruit jam, topped with white sugar icing

Nectarines

Orange Creams – in individual glasses

Oranges

Pears in wine

Pistachio Creams – in individual glasses

Pistachio Nuts

Plums

Pots de Crème – individual baked custards

Pralines – almonds covered in in hard caramelized sugar

Profiteroles – cream puffs

Puits d’Amour (Wells of Love) – cylindrical puff-pastry cases filled with redcurrent or raspberry jelly, and glazed with caramel

Raspberry Creams – in individual glasses

Ribbon Creams – different flavors of cream, layered in individual glasses, with colored sweetmeats separating the layers

Small Glazed Cakes in Assorted Colors

Snow Balls – baked cored apples filled with marmalade, inside a pastry shell, and covered with white sugar icing

Spanish Cream – flavored with rosewater, in individual glasses

Strawberries and Cream

Strawberry Ice Cream

Tarte Conversation – puff pasty shells filled with almond cream, covered with hard sugar icing

Trifle – liquor-soaked macaroons topped with flavored cream.

Vanilla Ice Cream with Honey

Walnuts

White Nougat

Further Reading

Black, Maggie, and Deidre Le Faye. The Jane Austen Cookbook. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1995.

Clair, Colin. Kitchen & Table. New York: Abelard-Schulman, 1965.

Camporesi, Piero. Exotic Brew. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994.

Flandrin, Jean-Louis. Arranging the Meal: A History of Table Service in France. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007.

Fleming, Elise. “Of Course It’s ‘Course’! Remove ‘Remove’!” Confections and Cakes. 20 January 2017.

Harrison’s British Classicks: The Connoisseur, The Citizen of the world, and The Babler. London: Harrison & Company, 1786.

Hartley, Dorothy. Food in England. London: Macdonald & Co., Ltd., 1962.

Howard, Henry. England’s Newest Way in all Sorts of Cookery, Pastry, and all Pickles that are Fit to be Used. London: Chr. Coningsby, 1708.

Kisban, Eszter. "Food Habits in Change: The Example of Europe." Food in Change. Fenton, Alexander & Eszter Kisban, eds. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers, Ltd., 1986.

la Chapelle, Vincent. The Modern Cook. London: Nicolas Prevost, 1733.

Lane, Maggie. Jane Austen and Food. London: The Hambledon Press, 1995.

Larkin, Peter, ed. Richard Coer de Lyon. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2015.

Mennell, Stephen. All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Palmer, Arnold. Movable Feasts. London: Oxford University Press, 1953.

Raffald, Elizabeth W. The Experienced English Housekeeper. London: R. Baldwin, 1782.

Rochefoucauld, François de la. A Frenchman’s Year in Suffolk. Trans. Norman Scarfe London: Boydell Press, 1988.

Root, Waverley. Food. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1980.

Strutt, Joseph. A Complete View of the Dress and Habits of the People of England, from the Establishment of the Saxons in Britain to the Present Time. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1878.

Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1989.

Verral, William. A Complete System of Cookery. London: William Verral, 1759.

Vogler, Pen. Dinner with Jane Austen: Menus Inspired by Her Novels and Letters. London: Cico, 2023.

Vogler, Pen. Dinner with Mr. Darcy: Recipes Inspired by the Novels and Letters of Jane Austen. London: Cico, 2020.

White, Gilbert. The Natural History of Selborne. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, Penguin Books Ltd., 1977.

Enjoyed this research post? Consider fueling my research endeavors with a fresh brew: