Marriage Annulments in Georgian England: From "I Do" to "I Don't"

- Paullett Golden

- Aug 18, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Aug 28, 2025

Publication Date: August 18, 2025

“A girl likes to be crossed a little in love now and then. It is something to think of.”

"We Were Never Truly Married..." The Rare, Rigid, and Really Complicated World of Regency Annulment

Between the pages of Regency romances, annulments often seem as simple as a heroine tossing her ring at her husband and declaring, “This marriage never happened!” But in the real Georgian era? No such luck! An annulment wasn’t a get-out-of-marriage-free card, nor was it about being disappointed, disillusioned, or even heartbroken. To annual a marriage under English law, one had to prove it had never been valid to begin with, which was no easy feat. While a divorce acknowledged a marriage took place and was now at an end, an annulment marked there never was a marriage, no matter who said "I do." To declare there never was a marriage, ceremony or not, annulment cases became a legal labyrinth, steeped in ecclesiastical red tape and social scandal. Let’s dive into the rigid rules, debunk the myths, and unearth some jaw-dropping real cases that show just how messy love and law could get in 18th- and early 19th-century England.

Annulment vs. Divorce: A Vital Distinction

Annulment

Annulment meant the marriage was void or voidable from the start, never legal, never binding.

An annulment wasn't an “undo” button for a bad marriage, rather it declared the union null and void, as if it had never existed. This had massive consequences: any children became illegitimate, inheritance rights would be lost, and there could be a restriction on remarriage within the church since an annulment was ecclesiastical (in such cases, it was the clergy refusing to marry someone party to an annulment since this was seen as a moral issue).

Annulments were extraordinarily rare, as they fell under the Church of England’s ecclesiastical courts, governed by canon law, not civil courts. These courts prioritized marriage as a sacred bond, so proving invalidity meant navigating a moral and legal minefield, often with public humiliation as the price, and as we know all too well, reputation was everything in this era.

Divorce

Divorce meant the marriage had been valid but was now legally ended (an extremely rare outcome, requiring an Act of Parliament, and thus best saved for a future blog post!).

Since divorce acknowledged a marriage’s validity, it required a grueling three-step process: a civil suit for “criminal conversation” (adultery), an ecclesiastical separation, and a private Act of Parliament. Between 1765 and 1857, only 276 divorces were granted, and just four to women, making annulments a slightly less impossible dream—but still a nightmare to obtain. Depending on the reason for divorce, the guilty party may be barred from remarriage.

“All the privilege I claim for my own sex (it is not a very enviable one, you need not covet it) is that of loving longest, when existence or when hope is gone.” -Persuasion

Valid Grounds for Annulment

To annul a marriage, one had to prove it was either void (never legal to begin with) or voidable (valid until challenged). Do you recognize those two terms from A Counterfeit Wife? These appeared as part of the discussion between the Marquess of Pickering and his solicitor, who explains their legal avenues for annulling the marquess’ fraudulent marriage to Phoebe Whittington.

To successfully annul a marriage, one of the following had to be proven:

Bigamy: If the spouse was already married, the new marriage was void. But it had to be proven that the first marriage was valid and the spouse still alive—no easy task without modern records, and additionally complicated when you consider the clandestine weddings that took place in Scotland and elsewhere. For example, in 1815, actress Harriot Mellon’s marriage to banker Thomas Coutts was declared illegal after his family challenged its validity due to the irregularity of a missing witness. The couple, then, had to remarry months later to secure their union. (What’s a successful marriage without the loving care of one’s family, right?)

Fraud or Identity Deception: Marrying under a false name, concealing a prior pregnancy by another man, or misrepresenting status (e.g., promising a dowry that didn’t exist) could void a marriage. Bishops sometimes overlooked minor name errors if the intent was honest (A Counterfeit Wife spring to mind?), but deliberate fraud was a dealbreaker. In fiction, this is a juicy plot device, but real cases were rare due to the scandal involved. Honestly, with such a scandal, it’d be better to stay married to the fraud! And no, court cases could not be kept private, as all cases were publicly published and sold in the streets of London for gossipers to grab, read, and regale about to their friends.

Consanguinity or Affinity: The Church’s table of “kindred and affinity” banned marriages between close relatives, like a widower marrying his deceased wife’s sister. (Yes, this very scenario is often found in historical romances, but it would have been illegal at the time.) These marriages were voidable. The caveat? A couple could get away with it if no one knew, but if challenged during both parties’ lifetimes, the marriage would be voided. Marrying a cousin, however? Totally fine (and encouraged among the elite).

Underage Marriage Without Consent: Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753 required parental consent for those under 21 if married by license (not banns). Without it, the marriage was voidable—but only if a parent pushed for annulment, which was rare to avoid ruining the bride’s reputation. After 1823, residency rules tightened, but annulments for this reason remained uncommon.

Lack of Proper Ceremony: That elopement to Gretna Green? Totally voidable. The 1753 Act mandated marriages occur in a parish church after banns or with a license, witnessed by two people and recorded. Marriages missing these steps—like those clandestine elopements we so often read about—could be voided (and likely would be voided if the young lady was of aristocratic lineage since the bridegroom was most likely inferior, a rogue, and/or a fortune-hunter). How about a super juicy example? Try this one! Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex, saw his 1793 marriage to Lady Augusta Murray annulled because it violated the Royal Marriages Act of 1772, lacking King George III’s consent.

Impotence: This wasn’t about non-consummation but permanent inability to consummate. Proving this was extensive, humiliating, and invasive, not to mention a public ordeal: the man faced medical exams, and the woman had to prove her virginity, often via invasive inspections (more on this to come). Witness testimony was often required, as well, as in household staff or family who could vouch that hanky panky had not and could not occur (let’s not think of just how the staff and family would come about this knowledge, eh?). An 1820 case (Norton vs. Seton), detailed in ecclesiastical court reports, shows how rarely this succeeded—one man was annulled for impotence, only later to father a child, sparking debate about overturning the ruling (can you imagine what chaos that could have caused!?). For more impotence cases, check out Hoffman's article, "Behind Closed Doors: Impotence Trials and the Trans-Historical Rights to Marital Privacy."

Insanity or Incompetence: If one party was deemed insane at the time of the marriage, it could be annulled for lack of consent. (Pity Mr. Rochester couldn’t have proven Bertha’s insanity sooner, eh? Jane Eyre could have had her wedding day!) In 1814, John Wallop, 3rd Earl of Portsmouth, married Mary Anne Hanson, but his family later proved he’d been insane since 1809. The marriage was annulled in 1828 after a lengthy inquiry, leaving Hanson socially ostracized. Take a moment to consider two factors with that example—it took over a decade to secure the annulment, during which time, she remained married to him (and had 3 children), AND the whole of the scandal completely ruined her social standing and future (she had to flee abroad). One must ask, was it worth it?

Each ground carried risks: annulments made children illegitimate, stripped inheritance (especially titles), and often left the woman’s reputation in tatters, as she was demoted from wife to “concubine” in society’s eyes.

Common Myths About Annulments

Regency romances love to fling annulments around like confetti, but the reality was far less romantic. Here are the top myths (aka plot devices often found in our most favorite of books—sorry!):

Myth 1: “We never consummated the marriage, so we can annul it.”

Nope! Non-consummation was not a reason for annulment. The only way this was viable was if the husband was impotent, in which case, you had to prove permanent impotence (and not a “disinterest” kind of impotence either, but medically impotent), and this, as we previously covered, meant humiliating exams and testimony. Even after medical examinations and witness testimony, success was RARE—courts knew arousal could be selective (yes, they debated this!) and so were not quick to believe impotence could really be permanent. The myth persists in novels, but in reality, couples stuck in unconsummated marriages would have to pursue legal separation instead (i.e. divorce).

Myth 2: “We eloped without parental consent, so it doesn’t count.”

Not quite. If you were over 21 or used a license, the marriage was binding, consent or not. As for a marriage by banns, parents could block the banns from being read in the first place, or during the three calls, they give reason to the pastor why the couple could not be married. If the couple managed to marry by banns before the parents could contest, however, the parents couldn’t annul the completed marriage unless fraud was proven in court (e.g., lying about consent, especially if on a license). This myth fuels dramatic elopement plots, but most families grudgingly accepted such unions to avoid scandal, and anything involving the courts, civil or ecclesiastical, would have been quite scandalous.

Myth 3: “They left me—surely that invalidates the marriage?”

Nope. Abandonment was a heartbreak, not a legal out. It might justify a legal separation (divortium a mensa et thoro), but annulment required proving the marriage was invalid from day one. Deserted spouses often had to endure social stigma and financial limbo, especially women, who had no legal identity apart from their husbands.

Myth 4: “Annulments were quick and discreet.”

Hardly! Ecclesiastical court trials were public, with testimony printed in newspapers and court reports. The process could drag on for years, and the social fallout was brutal—especially for women, who faced complete and total ruin while men often skated by with less damage.

Recent studies, like Rebecca Probert's Marriage Law and Practice in the Long Eighteenth Century, confirm these myths stem from modern misreadings of Regency novels, not historical records. Authors like Jane Austen avoided annulment plots, focusing instead on the social pressures of marriage, because they knew the legal reality was far less forgiving.

You Had to Prove... What?

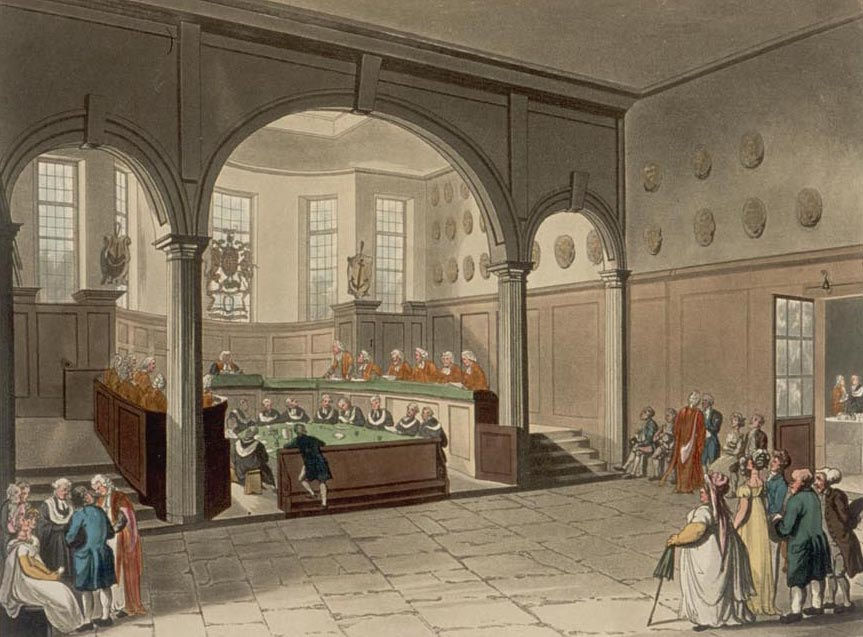

Annulments were tried in ecclesiastical courts, under the jurisdiction of the Church of England. Bishops and canon law held sway. These weren’t cozy courtrooms but moral battlegrounds, blending church doctrine with legal scrutiny. To prove your case, you needed ironclad evidence, often at great personal cost:

For Bigamy: Produce a valid prior marriage record and proof the first spouse was alive. This could involve tracking down parish registers or witnesses across counties—no small feat in an era of spotty documentation.

For Fraud: Show deliberate deception, like a false name or hidden pregnancy. Courts required documents (e.g., marriage settlements) or witness testimony, but bishops often leaned toward preserving marriages to avoid scandal. (Read the last part of that sentence again! Yes, even if fraud, deception, etc. were proven or provable, bishops would do all in their power to ensure the marriage stayed intact regardless. Something to consider when thinking of the ending of A Counterfeit Wife, eh?)

For Insanity: Prove the spouse was legally incompetent at the time of the vows, often requiring years of medical records or family testimony. The Portsmouth case (1814–1828) involved a decade-long inquiry into the earl’s mental state, with his family’s wealth and title at stake.

For Impotence: This was the stuff of nightmares. The man faced physical exams by surgeons (among other… ahem… methods), while the woman had to prove her virginity—often via invasive medical checks (and let’s hope she’s not an avid horse rider). “Bed witnesses” (servants or others who could testify about the couple’s private life) were sometimes called, making the process a public spectacle. In one 1820 case, a man’s annulment was nearly reversed when he later fathered a child, as courts debated whether impotence was situational. Proving impotence was a public ordeal that left no stone unturned—or dignity intact. Men faced medical exams by surgeons to check for physical defects, and no, despite juicy rumors, prostitutes weren’t paraded in to test arousal (though earlier European courts toyed with such ideas!). Instead, “bed witnesses”—servants or others—might spill intimate details about the couple’s failures. Women had it worse: they had to prove their virginity through invasive exams by midwives, checking for an intact hymen. But here’s the kicker—horseback riding, dancing, or even natural variation could “erase” this proof, leaving active women at risk of being deemed unchaste, even if innocent. Courts occasionally accepted medical explanations, but the process was a humiliating gamble.

If you’re curious to learn a bit more about the medical exams for both parties, read on. If not, skip down to the final comments in this section, just before the cheat chart.

Medical Exams for Men: To prove impotence, courts required a physical examination of the man by court-appointed surgeons. These exams focused on anatomical or physiological defects (e.g., deformities or injuries) that could prevent consummation. If you’ve ever read in a novel or blog about “arousal tests,” such as the surgeons bringing in a prostitute to test true incompetence, this was not a method used during the Georgian era. It was, however, a method used in earlier times (Medieval England, anyone?). During the Georgian era, these exams were more about observing physical capability than staging a provocative scenario. For example, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Ecclesiastical Courts at Doctors’ Commons (1810–1820) describes cases where surgeons examined men for “natural defects” (no mention of prostitutes or otherwise).

The “Congress” Rumor: The idea of using prostitutes to “test” the husband comes from earlier European practices, particularly in medieval and early modern France, where “congress” trials (pre-1650s) occasionally involved a couple attempting consummation under observation to prove or disprove impotence. These were rare and phased out by the 18th century. There’s no record of them that I can find in England’s ecclesiastical courts during the Georgian era.

Selective Arousal Debate: Courts did recognize that impotence could be situational (e.g., only with the spouse), which complicated cases. In Norton vs. Seton (1820), as I mentioned before, a man’s annulment was questioned when he later fathered a child, suggesting courts were skeptical of “temporary” impotence claims. However, no records confirm prostitutes or similar were used to test this; instead, testimony from servants or “bed witnesses” about the couple’s private life was more common.

Reminder of the Times: The Regency era was prudish about public morality (despite private scandals), and ecclesiastical courts aimed to maintain dignity, even in messy cases. Involving prostitutes or attempting a “congress” test would’ve been scandalously improper and unlikely to pass muster with church officials. Want to learn more about what was (and wasn’t) reported in annulment cases? Check out The Gentleman’s Magazine of the era, as it loved to report salacious courtroom gossip, especially with annulment cases!

Medical Exams for Women: In most of the annulment case alleging impotence, the wife had to prove her virginity to confirm the marriage was unconsummated. This was typically conducted by midwives or physicians, and they were specifically checking for the presence of the hymen. With even the most basic knowledge of female anatomy plus modern medical knowhow, the modern reader might recognize the myriad issues with this sort of exam. Let’s dig into this just a little bit further.

Medical Knowledge in the Regency Era: Believe it or not, the Regency-era medical community was aware, to some extent, that physical activities such as horseback riding, dancing, or even accidents could rupture the hymen without sexual activity, which could complicate an annulment case based on impotence.

Virginity Exams: Ecclesiastical courts required women in impotence-based annulment cases to undergo examinations to verify they hadn’t consummated the marriage or borne children by another man. The midwives or female inspectors (called “matrons”) who conducted the exams focused on the hymen as their primary indicator of virginity. Lawrence Stone’s Road to Divorce: England 1530-1987 notes that these were “invasive and distressing,” as you can imagine, especially considering the results were publicly discussed in court.

Hymen Misconceptions: However limited Georgian medical knowledge might have been, it wasn’t entirely ignorant. Consider, for example, William Cullen’s First Lines of the Practice of Physic (1780s), which acknowledged that the hymen could be absent or damaged due to non-sexual causes, such as exercise, horse riding, trauma, nature, etc. Some women are born without a detectable hymen, and this is noted in the medical literature of the 18th century (don’t get me started with all the flaws in steamy romances, especially when the “missing hymen” is used as a plot device. Grumble, grumble, scowl.).

Impact on Cases: If that legendary hymen was absent, it could weaken her case since the courts leaned on physical evidence over testimony, but midwives and enlightened physicians could testify to the reason for the absence, such as the common knowledge of the woman’s rigorous horseback riding (which was especially popular amongst aristocratic women). In Rebecca Probert’s Marriage Law and Practice in the Long Eighteenth Century, we have confirmation that while virginity was scrutinized, exceptions were sometimes made for “natural” hymen loss.

Social Stakes: Now, that said, a woman failing to “prove” virginity did face several social consequences, even if completely innocent, namely being labeled unchaste. This made the process doubly cruel (especially for active women who enjoyed sports and horse riding). In The Diary of Caroline Powys, we have a hint at society’s harsh judgment of women in such cases, which certainly amplifies the stakes.

The process was costly, public, and brutal. Court records, like those in Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Ecclesiastical Courts at Doctors’ Commons, show trials packed with salacious details, eagerly consumed by the gossip-hungry public. No one walked away with their dignity intact.

Annulment Quick Cheat Chart

Ground | What It Means | Proof Needed |

Bigamy | Spouse was already married to someone else, making the new marriage void. | Valid prior marriage record; proof the first spouse was alive (e.g., witnesses). |

Fraud or Identity Deception | False identity, hidden pregnancy by another man, or major lies (e.g., fake dowry). | Documents (e.g., marriage settlement); witness testimony proving deliberate fraud. |

Consanguinity or Affinity | Marriage to a close relative (e.g., sibling) or prohibited in-law (e.g., deceased spouse’s sister). | Family records showing relationship; challenge during both parties’ lifetimes. |

Underage Marriage Without Consent | One party under 21 married without parental consent (if using a license). | Marriage record showing age; proof of missing consent (e.g., no parental sign-off). |

Lack of Proper Ceremony | Marriage skipped banns/license, used an unqualified officiant, or lacked witnesses. | Parish records; evidence of missing banns, license, or witnesses (e.g., register). |

Impotence | Permanent inability to consummate the marriage, not just non-consummation. | Medical exams (for both parties); testimony from “bed witnesses”; virginity proof. |

Insanity or Incompetence | One party was mentally incompetent at the time of the vows, negating consent. | Medical records or expert testimony proving insanity at the time of marriage. |

Case in Point: Real Marriage Annulments That Shocked Society

Mary Wharton

In a rather scandalous case (a few years before the Georgian era began) heiress Mary Wharton was abducted and forced into marriage at just 13 years old by the Honorable James Campbell of Burnbank and Boquhan, 30 at the time. To evade punishment, Campbell fled to Scotland. The case? Mary Wharton and James Campbell Marriage Annulment Act 1690. The players? Captain James Campbell, the fourth son of the 9th Earl of Argyll, and Mary Wharton, the granddaughter of Sir Thomas Wharton and heiress to Goldsborough Hall and a sizable income. Campbell did not act alone, rather had several friends aid him in forcing her into a six-horse coach and whisking her away to be wed. Interestingly, the 10th Earl of Argyll (Campbell’s older brother, and eventually 1st Duke of Argyll) attempted to petition against the annulment to ensure the two remained wed. Eek!

Prince Augustus and Lady Augusta Murray

When Prince Augustus, Duke of Sussex, secretly married Lady Augusta Murray in 1793, he defied the Royal Marriages Act of 1772, which required the king’s consent for royal unions. King George III had the marriage annulled in 1794, declaring it void for lack of approval. The couple’s two children were deemed illegitimate, and Augusta was shunned by the court. This high-profile case, widely reported, underscored how even royalty couldn’t escape the law’s iron grip. This case, by the way, is worth looking further into, especially as to what happened after the annulment.

John Wallop, 3rd Earl of Portsmouth

John Wallop’s 1814 marriage to Mary Anne Hanson was annulled after his family proved he’d been insane since 1809. The lengthy inquiry (which was mentioned in the insanity section previously), involving medical experts and family testimony, exposed his mental instability at the time of the vows, rendering the marriage voidable and her three children illegitimate. Hanson, the daughter of Wallop’s solicitor, faced social ostracism so profound she fled abroad. The case was a wild one, and neither party was without guilt of some kind.

Harriot Mellon and Thomas Coutts

When actress Harriot Mellon married wealthy banker Thomas Coutts, his family was outraged, suspecting her of gold-digging. They challenged the marriage’s validity, claiming a procedural error (possibly a missing or added witness). The marriage was declared illegal in March 1815, forcing a second ceremony in April. This case, noted in Regency History, shows how even minor technicalities could trigger annulment battles, especially when wealth and status were at stake.

These cases, drawn from historical records, reveal the social and legal chaos annulments unleashed. Recent studies, like Lawrence Stone’s Broken Lives: Separation and Divorce in England 1660–1857, emphasize how these public spectacles fed society’s appetite for scandal while reinforcing marriage’s permanence. There are some wild cases out there worth perusing. Could you stumble on a Regency letter describing a young lady claiming to have mistaken her cousin’s valet for her betrothed, only to receive the court’s ruling of “deception not sufficient cause for annulment without evidence of fraud”? Maybe! wink

Concluding Thoughts

The fun of writing fiction, even historical fiction, is just that; it's fiction! Grounding plots within the real, historical laws provides ample enough writing fodder, but what writer does not break the rules from time to time for our entertaining and reading pleasure? So, tell me, what is the wildest marriage plot twist you have read in an historical romance?

Some Great Sources

Rachel Knowles, “Regency: When Could Marriage Be Annulled,” Regency History https://www.regencyhistory.net/blog/regency-when-could-marriage-be-annulled

Historical Hussies’ “Annulments, Separations, Divorce, and Scandal,” Historical Hussies https://historicalhussies.blogspot.com/2013/05/annulments-separations-divorce-and.html

Stephanie B. Hoffman, Behind Closed Doors: Impotence Trials and The Trans-Historical Right to Marital Privacy, Boston University Law Review, Vol. 89 (2009)

John Haggard, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Ecclesiastical Courts at Doctors’ Commons (2010)

(available free via archive.org, HathiTrust, GoogleBooks, and a number of other places, including purchasable through Amazon). Packed with real annulment cases, including Norton vs. Seton (1820), these reports offer unfiltered glimpses into the legal process and its drama. Happy reading!

William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, Books I and III (1765–1769)

Blackstone’s work is the gold standard for understanding Georgian legal frameworks, including marriage and annulment. You can find digitized versions here at Yale’s Avalon Project or other places, such as at Project Gutenberg, archive.org, and beyond.

The Diary of Caroline Powys (1756–1808)

AKA the Diaries/journals of Mrs. Philp Lybbe Powys (née Girle). You’ve seen me reference this one before! Powys’s diaries offer a woman’s perspective on Georgian social norms, with subtle hints at marriage scandals. You can find it free on archive.org and a few other places, or purchase it on Amazon.

Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce: England 1530–1987 (1990)

You should know already how much I adore Stone’s works, as I cite him often. This particular work is a classic, blending legal history with vivid case studies. Stone details how annulments were rarer than divorces but equally scandalous. Give it a search, and you’ll find it for purchase on Amazon or free at archive.org, JSTOR (my fave!), or elsewhere.

Rebecca Probert, Marriage Law and Practice in the Long Eighteenth Century (2009)

Probert’s meticulous research debunks myths (like non-consummation) and clarifies Hardwicke’s Act’s impact. A must-read for legal nerds. You can spy this one on Google Books, Cambridge University Press, Amazon, and other places.

R.B. Outhwaite, Clandestine Marriage in England, 1500–1850 (1995)

Explores irregular and dodgy marriages and their legal fallout and tangles, including annulments triggered by procedural errors and some that were later contested (oh my!). Google Books has it, as does Cambridge University press, Amazon, and a few other places.

Joanne Bailey, Unquiet Lives: Marriage and Marriage Breakdown in England 1660–1800 (2003)

A recent study offering fresh insights into how annulments affected women’s social status, with data on case outcomes. Snag this beauty from archive.org, Amazon, Cambridge University Press, or elsewhere.

Fun Extra: Check out The Gentleman’s Magazine (1731–1907), digitized on HathiTrust for your reading pleasure, as it often reported annulment scandals alongside society gossip. It’s a treasure trove for Regency drama!

Enjoyed this research post? Consider fueling my research endeavors with a fresh brew: