The Languages of Regency England: From Refinement to Espionage

- Paullett Golden

- Jul 11, 2025

- 12 min read

Publication Date: July 12, 2025

“A lady without French is like a gentleman without a sword—unarmed in the face of society's battles.”

Intro: The Linguistic Art of Regency Refinement

In the glittering ballrooms and candlelit drawing rooms of Regency England (1811-1820, strictly speaking, or 1790-1830 for the long Regency), a lady or gentleman's polish wasn't measured solely by a perfectly tied cravat or a graceful curtsey. Language was a dazzling accessory, wielded with the same finesse as a silk fan or a well-timed quip. For the well-bred, fluency in certain tongues was as essential as a town carriage—a mark of status, education, and cosmopolitan charm. The languages a person knew varied by rank, profession, and ambition.

An aristocrat destined for diplomacy might toss off French with diplomatic ease, while a merchant’s son in the East India Company grappled with Portuguese ledgers. A gently bred lady might pen Italian poetry, while her brother conjugated Latin verbs to prove his scholarly mettle. Yet, regardless of station, a core set of languages defined the elite’s education. These weren’t just tools for communication but symbols of refinement, opening doors to flirtation, culture, and intellectual flexing.

Let’s explore the languages that Regency ladies and gentlemen were expected to know, from the flirtatious French of Almack’s to the dusty Latin of Oxford’s halls, and uncover how they used these tongues to navigate their dashing world.

French: The Lingua Franca of Elegance and Espionage

French was the language to know above all others. It was the undisputed queen of languages in Regency England, as essential to a person of quality as a season in London. It was the language of diplomacy, high culture, and le bon goût (good taste). No self-respecting lady or gentleman could afford to be ignorant of French—it was the key to navigating elite society, from decoding Parisian fashion plates to gossiping discreetly at a ball.

Fluency in French was practically a birthright for the aristocracy and gentry. Governesses and tutors drilled young ladies and gentlemen in French grammar, pronunciation, and etiquette from childhood, often using texts like Voltaire’s Candide or Madame de Genlis’ educational manuals. Ads were often posted for governesses "proficient in French and music," for what is a lady without the tongue of Paris to adorn her? Finishing schools for ladies, such as those in Bath, emphasized French alongside dancing and deportment.

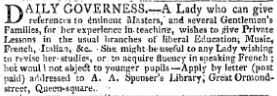

In this ad excerpt from 1815, we see a need for a governess who is fluent in both French and Italian, and interestingly, there's a double emphasis on French:

A lady might pen a letter in French to a modiste in Paris or sprinkle her conversation with phrases like “C’est la vie” to signal her sophistication—without, of course, veering into pretension. Jane Austen, ever observant, peppered her novels with French phrases—think of Mary Crawford’s je ne sais quoi in Mansfield Park—reflecting its ubiquity in polite society. Reading Molière and Rousseau or translating passages from Les Confessions? Very proper. Gossiping in French at Almack's to veil your scandalous observations? Even better.

Gentlemen, too, relied on French for more than flirtation. It was the language of international diplomacy, used in treaties and correspondence with European courts. During the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), French took on an extra layer of intrigue: émigrés fleeing the French Revolution often taught French to English families, and spies reportedly used it to pass coded messages.

Fun fact: French wasn’t just for the elite! More humble families aspiring to gentility hired French tutors, and advertisements in The Times, The Morning Post, or even The Morning Chronicle, for governesses “proficient in the French tongue.” Even servants in grand households might pick up a smattering of French to follow their employers’ orders or eavesdrop on their scandals.

Italian: The Language of Passion, the Grand Tour... and Mischief

If French was for flirtation, Italian was for passion. Italian was the language of romance, music, and wanderlust, second only to French in Regency hearts. Its melodic cadence made it a favorite for those who fancied themselves cultured cosmopolitans.

For gentlemen, Italian was a staple of the Grand Tour, the rite-of-passage journey through Europe (particularly Italy) that young aristocrats undertook to complete their education. Accompanied by their long-suffering tutors or “bear-leaders,” they studied Italian to navigate Rome’s ruins, haggle in Venetian markets, or woo local beauties with Petrarchan sonnets. Lord Byron, the Regency’s bad-boy poet, famously immersed himself in Italian culture, writing letters and poetry in the language during his travels.

For ladies, Italian was less about travel and more about art and emotion. Opera was the height of fashion in London’s King’s Theatre, where stars like Angelica Catalani sang in Italian. A lady who could follow a libretto or hum an aria from Il Barbiere di Siviglia earned serious cultural cred. You might recognize this gem from one of Lady Caroline Lamb's letters: "Italian is the language of the heart, and I confess I studied it more for Signor Catalani's arias than for any Grand Tour."

Italian was also a staple in ladies’ commonplace books, where they copied romantic verses from Dante or Tasso, often alongside their own poetry. While ladies spoke Italian less frequently than they wrote it, a whispered “Caro mio” at a Vauxhall Gardens concert could set hearts aflutter.

Italian’s popularity wasn’t universal, though. It was considered less essential than French, and fluency often depended on personal interest or a family’s travel plans. Still, its association with music and the arts made it a glamorous addition to any education.

Latin: The Gentleman's Badge of Learning, aka The Scholarly Spine of a Gentleman's Education

Latin was the bedrock of a gentleman’s classical education, a badge of intellectual rigor that separated the truly learned from the merely wealthy. Boys of the gentry and aristocracy began studying Latin as young as seven, often at public schools like Eton or Harrow, where they memorized (yes, memorized) Cicero, Virgil, and Horace. Mastery of Laton was a prerequisite for university (i.e. Oxford or Cambridge), the clergy, law, or politics. To know Latin marked one not only as educated, but as being of Quality with a capital Q. It signaled not just education but moral discipline—after all, anyone who could conjugate amo, amas, amat for hours was clearly made of stern stuff!

While Latin was rarely spoken conversationally (and certainly not mid-dance at a ball, unlike French and Italian), it was far from dead. As Samuel Johnson implied of Latin in his essays, "Latin is the gentleman's shield, to be brandished in Parliament or the pulpit, but never at a ball." Gentlemen sprinkled Latin quotations in parliamentary speeches, letters, and even novels to flex their erudition. For example, Sir Walters Scott’s characters in Waverley toss off Latin phrases to underscore their learning. Legal documents and court proceedings had only recently shifted to English in 1733, so “Law Latin” lingered in legal jargon. Even clergymen used Latin in sermons to impress (or confuse) their congregations.

Ladies, however, were rarely taught Latin, as it was deemed too scholarly for their “delicate” minds. Exceptions existed—bluestockings like Elizabeth Carter translated Latin texts, and some aristocratic women studied it privately—but it remained a male domain. A lady who knew Latin risked being labeled a pedant, though a clever one might slyly quote Ovid in her diary to vent her frustrations.

Greek: The Scholar's Extra Credit

For the most ambitious gentlemen, Greek was the cherry on top of a classical education. Less common than Latin, it was studied by those aiming for Oxford, Cambridge, or the clergy, where reading Homer, Plato, or the New Testament in the original Greek was a mark of distinction. As an 1812 Oxford tutor wrote to a student's father, later quoted in The Gentleman's Magazine, "Greek is a young man's trial by fire, proving he can wrestle with Homer before he wrestles with life." Greek was rarely used outside academic or intellectual flexing, but it added weight to a gentleman’s scholarly resume. For example, a young man might translate Thucydides to impress a university don or pen a Greek epigram to show off at a dinner party. Ladies almost never studied Greek, making it an exclusively masculine pursuit.

What About Other Languages? German, Spanish, Portuguese, and Beyond

While French, Italian, and Latin dominated polite education, other languages cropped up depending on a person’s circumstances. German gained traction among intellectuals, especially after the 1800s, when German literature (Goethe, Schiller) and philosophy (Kant, Hegel) became fashionable. Aristocrats with ties to the Hanoverian court—King George III was a German prince, after all—might learn German for diplomacy or to read Faust in the original. However, it was less common than French or Italian, as Germany was not a prime Grand Tour destination.

Spanish and Portuguese were niche but vital for those engaged in trade or diplomacy. The East India Company and the Royal Navy dealt extensively with Spanish and Portuguese colonies, particularly in South America and India. Portuguese was especially prominent in India, where it had been the language of trade since the 16th century, and still was in the 18th century, although by the Regency era, English was overtaking it as British colonial influence grew. A merchant’s son in Bombay or Calcutta might learn Portuguese to negotiate with local elites who clung to older trade networks, while a diplomat in Lisbon during the Peninsular War (1808–1814) needed Spanish or Portuguese for negotiations.

Other languages, like Dutch or Russian, were rare and typically learned only by those with specific business or diplomatic needs. For example, a naval officer stationed in the Baltic might pick up some Russian to parley with allies, but such cases were exceptions, not the rule, in the Regency world.

Language as Social Currency: The Art of Linguistic Showmanship

In the Regency era, languages were more than tools—they were social capital. A well-placed French phrase at a ball could signal refinement; an Italian aria sung at a musicale could spark romance; a Latin quotation in Parliament could win respect. Yet, there was a fine line between charm and ostentation. Overusing foreign phrases—especially Latin—could earn you a reputation as a pompous bore, as Jane Austen’s Mr. Collins demonstrates with his clumsy attempts at learnedness.

Ladies faced an even trickier balance. A woman who spoke French too fluently risked seeming “fast,” while one who quoted Latin might be labeled a bluestocking (instant death to one's social life and reputation!). The ideal was effortless elegance: enough fluency to impress without overshadowing one’s grace or modesty.

For gentlemen, languages were a proving ground—Latin for the scholar, French for the diplomat, Italian for the rake (take note, authors!). In both cases, the true art was wielding language like a Regency dandy’s cane: with style, confidence, and just a hint of mischief.

Language in Context: Navy, Trade, and Women's Literary Circles

Languages in the Regency weren’t just for showing off at balls—they were practical tools in specific arenas, from stormy seas to bustling trade ports to the intellectual salons of bluestocking ladies. Here’s how French, Italian, and others played out in three distinct worlds.

The Navy: Multilingual Maneuvers at Sea

For officers in the Royal Navy, languages were as vital as a well-aimed cannon. The Napoleonic Wars kept Britain’s fleet busy, and officers needed to communicate with allies, interrogate prisoners, or negotiate in foreign ports. French was indispensable, as it was the language of diplomacy and often used in parleys with French naval officers or neutral parties. Captain Horatio Nelson, for instance, reportedly used French to correspond with allies during Mediterranean campaigns. Spanish and Portuguese were also critical, especially in the Peninsular War, where British ships supported Spanish and Portuguese forces against Napoleon. A naval officer stationed in Lisbon or Cádiz might learn enough Portuguese or Spanish to haggle for supplies or charm local officials.

Less commonly, officers in the Baltic or Russian campaigns picked up smatterings of Russian or Dutch to coordinate with allies like the Swedish navy. While fluency wasn’t expected—sailors were more likely to know sea shanties than sonnets—these languages helped navigate the choppy waters of wartime alliances. As one naval officer, Captain Frederick Marryat, later wrote in his memoirs, “A few words of French or Spanish, well-timed, could save a ship or seal a treaty.”

Trade: The Tongue of Commerce

In the bustling world of Regency trade, languages were the currency of profit. The East India Company, a powerhouse of British commerce, operated across Asia, Africa, and the Americas, requiring its agents to dabble in multiple tongues. While English was increasingly dominant in India by the 1810s, Portuguese lingered as a trade language in ports like Goa, where it had been entrenched since the 16th century. Company men often learned Portuguese to deal with local merchants or read old trade records, though fluency was rare—most relied on interpreters for complex negotiations. In an 1817 East India Company report, it was expressed that there was a need for language skills in colonial trade. An extrapolation of the report: "A merchant without Spanish or Portuguese is as lost in the Indies as a ship without a compass."

Spanish was equally vital for trade with South America, where British merchants eyed opportunities in colonies loosening Spain’s grip. A merchant in London’s counting houses might study Spanish to secure deals for textiles or sugar in Buenos Aires. German, too, had its place, especially for traders dealing with Hamburg or Bremen, key ports for British goods. As a 1818 advertisement in The Times boasted, “Wanted: a clerk fluent in German and Spanish for a mercantile house in the City.” For these men, languages weren’t just polish—they were profit.

Women's Literary Circles: The Bluestocking's Linguistic Playground

While gentlemen dominated Latin and Greek, women of the Regency’s intellectual elite—known as bluestockings—carved out their own linguistic niche. In literary salons hosted by figures like Lady Elizabeth Montagu or Hester Thrale, French and Italian were the stars. These women read Voltaire, Rousseau, and Madame de Staël in French, debating philosophy over tea. Italian was equally cherished, with many bluestockings translating Petrarch or Tasso for their own amusement or to publish in literary journals. Elizabeth Carter, a prominent bluestocking, translated Epictetus from Greek (a rare feat for a woman) and corresponded in French with European intellectuals.

These circles weren’t just about showing off. Languages allowed women to engage with ideas barred from them in formal education. A lady might pen a French essay for a literary society or copy Italian poetry to share at a salon, subtly challenging the notion that women’s minds were “too delicate” for scholarship. As Hester Thrale wrote in her diary, “French is my key to the world’s wisdom, and Italian my heart’s delight.” For these women, languages were both intellectual rebellion and social currency.

Concluding Thoughts

For fun, check out multilingual Lady Hester Stanhope, who used her French and Italian to navigate European courts, as well as Sir William Jones, who learned Sanskrit alongside European languages for his work in India.

A Regency lady or gentleman didn’t need to be a polyglot, but a command of French, a dash of Italian, and (for men) a solid grounding in Latin were the hallmarks of good breeding. These languages opened doors to travel, culture, and social maneuvering, whether flirting at Vauxhall, negotiating trade in Calcutta, or debating in Parliament.

Above all, they were tools for crafting an image of effortless sophistication—the ultimate Regency goal. The trick was knowing just enough to charm your company without sounding like you were showing off (or perhaps for the more pretentious of aristocrats, used for that very purpose, alongside a raised quizzing glass). So, next time you imagine a ball at Almack’s, picture the rustle of silk, the clink of glasses, and a whispered “Mon cher” or “Cara mia” sealing the deal on a dance or a dalliance.

Some Great Sources

Not to be missed is R.W. Chapman's The Letters of Jane Austen, for Austen occasionally uses and refers to French phrases and words in her correspondences, reflecting the language's ubiquity.

Another great source is Ingid Tieken-Boon van Ostade's The Sociolinguistics of Late Modern English, which includes discussion of how French vocabulary was integrated into English conversation as a status marker.

John Moore's Travels in Italy from 1790 is a terrific read since his Grand Tour letters reflect not only on his tour experiences but the value of Italian for travelers and opera-goers.

Speaking of the Grand Tour, how about Chloe Chard's Pleasure and Guilt on the Grand Tour? Saucy title, no? In this one, we have how language learning, particularly Italian, was framed as both educational and sensuous. waggles eyebrows

But let's not forget about the ladies. Have you read Gillian Russell's Women, Sociability and Theatre in Georgian London? This one touches on opera culture as a site for multilingual flirtation. Naughty!

Ah, but there's more!

William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England is famously full of Latin legal terminology. And yes, even Austen's contemporaries referenced this work! Personally, I found it a tremendous help when writing Rafe in A Sporting Affair since he liked to slip Latin legal terms into his dialogue and even inner thoughts.

No classical education was without this book: A Short Introduction to Grammar by William Lily—boys were often required to memorize it.

For something a bit more modern, try The Crisis of the Aristocracy by Lawrence Stone. Frankly, anything by Lawrence Stone is a must read! Stone breaks down the classical education for upper-class boys' schooling (including the emphasis on Latin, grammar, and rhetoric). It was Stone's works that were instrumental in helping me research for this old post: A Gentleman's Education. (Boy is that an old post!)

The Diary of Caroline Powys, 1757-1808 (also known as Mrs. Philip Lybbe Powys, née Caroline Girle) includes occasional mentions of lessons, tutors, and the importance of genteel accomplishments, like language learning.

Fanny Burney has quite a collection of published journals and letters that are must haves, from her posthumously published Journals and Letters of Madame D’Arblay to a collection of earlier diary entries with The Early Diary of Frances Burney.

The Gentleman's Daughter: Women's Lives in Georgian England by Amanda Vickery is one of my absolute favorite resources, and I've mentioned it in many research posts, so if you've been around for a bit, you've seen it before. This foundational work offers a ton of material on women's accomplishments and how languages fit into their perceived "value" in society. If you don't own this book, you need to!

Enjoyed this research post? Consider fueling my research endeavors with a fresh brew: