Real People. Real Conflict. Real Romance.

Historical Romance

in the style of Jane Austen

Nobility

Many of our heroes are aristocrats (always dashing, eligible bachelors, of course), but have you ever wondered at the difference between an earl and a duke, or why the heir is called Lord Such-and-Such even though he's not titled, why the younger son of an earl would be termed Mr. rather than Lord, or if it would be better to marry the marquess or the viscount? Hopefully we can answer a few of these questions as well as some you might not have thought to ask. Let's talk about titles! I'd like to touch on a few aspects: rank differences, secondary titles, courtesy titles, entails, and the word dowager.

We'll begin with a few terms: royalty, nobility, gentry. Interestingly, the rules for how these terms are used and what titles belong to which category differ throughout Europe. Royalty is reserved for the royal family. Nobility is the group of titled aristocrats that are below royalty but above the common people in caste. Nobles include duke, earl, marquess, viscount, and baron. Where a duke is placed in this hierarchy depends on the country, as in many countries, only the royal family will have dukedoms, and thus a duke falls into royalty rather than nobility. In England, a duke would fall under nobility unless he is a royal duke. Gentry refers to landowners who are not peers of the realm (think Mr. Darcy). Baronet, knight, and squire are part of the landowning (or "landed") gentry (technically commoners who have been promoted to the gentry caste by gift from the Crown for services rendered) rather than the aristocracy, although a baronet is oft considered an aristocrat (gotta love semantics) if you're using the word "aristocrat" to mean purely a social caste rather than title holding.

Antoine Jean Duclos' Le Bal Paré

Just a quick clarification before we move forward. A "peer" as we often see it in historical romances refers to the "peerage," comprising of "peers of the realm." The peers of the realm are the titled gentlemen who sit on the House of Lords. This begins with a man, let's call him Mr. Cecil Jones, who inherits or is awarded a title. Depending on the title, it could come with just the title, the title and an estate, the title and an estate and surrounding lands, or even the title and an estate and surrounding lands and a portion of the country to oversee (not to mention any other holdings that come with the title, such as a swanky house in London, a few country homes with great views, etc). Mr. Cecil Jones is still the humble Cecil Jones on the inside, but once he receives his writ of summons and letters patent, confirming his title and inviting him to take his seat as a member of the House of Lords, he is now a title holder. (On a side note, did you know you can watch the Parliamentary sessions, including the House of Lords? I'll leave this link here for your perusal.)

From this point forward, our good friend Cecil Jones is known for the title he holds rather than his humble self. Let's say he was granted the Earldom of Clematis. He will now and forever be referred to as Clematis. No one will ever call him Mr. Jones or Jones again. Ever. He is Lord Clematis, the Earl of Clematis, or just Clematis. The holdings of the title become the man's identity. He is now a peer of the realm. A peer is the person who holds the title. A son, daughter, wife, or otherwise is not a peer, as they are not title holders, nor do they sit on the House of Lords. This can sometimes seem deceptive with the use of courtesy titles, but we'll get to that in a moment.

For the record, the "lord" distinction is attached to the title, not the person, so it's always Lord Title rather than Lord Surname or Lord Firstname: Lord Clematis but never Lord Jones or Lord Cecil as neither Jones nor Cecil are titles. With that in mind, lord is used only in combination with the title, so you would not say Lord Cecil Jones, Earl of Clematis--eek!--the distinction goes with the title, not the man: Cecil Jones, Lord Clematis, or Cecil Jones the Earl of Clematis. I'm just going to drop this point here, and we can pick it up again in another newsletter to explore how and why: there are a few titles that follow the female line.

Now, let's take a closer look at nobles.

21st century House of Lords, sessions viewable on YouTube

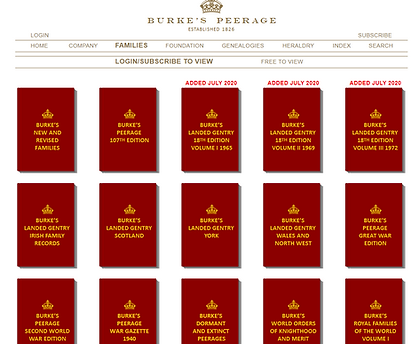

To begin this conversation, let's establish first that the ranks are not socially hierarchical, rather they serve different purposes within the governmental and political structure. There's a reason the Crown might grant the title of earl rather than marquess, or viscount rather than baron, and it's naught to do with social hierarchy or favoritism. Yes, they are politically hierarchical, but not socially. The age of the line and respect earned are what are socially valued, not the title itself. For instance, if there is a 12th Earl of Clematis available for marriage or the 1st Duke of Ivy, a family would push their daughter in the direction of the earl rather than the duke because the Clematis line is so well established--12 generations! Want to think like a marriage minded family? Find the beau you want based on family lineage in Burke's Peerage. A family wanting their daughter to marry well would not be vying for the "highest" member of nobility, such as a duke over an earl. Instead, a family would wish for their daughter to marry the bachelor who was most socially popular, most reputable, and with the most well-connected family, regardless of title or political hierarchy, hence the family might prefer the viscount who is on everyone's must-invite list rather than the reclusive earl no one has seen in a decade, or even possibly the second son of an earl over a viscount, as we see hinted to in A Dash of Romance. The socially popular bachelor with the distinguished lineage is the one with the power. The most well-networked bachelor is the one with the power.

Burke's Peerage Page Teaser

Now, let's break down the nobility to understand the differences and purposes of each title and what sort of land holdings they have or oversee. Save this source if you've not already done so, as it is the definitive guide to the peerage: Debrett's.

A duke possesses a dukedom (the title and rank) and oversees a duchy (the physical territory of rule). (Note: this is pronounced dyouk or djuk, not dook, emphasis on that you or ju sound to rhyme with puke rather than kook (humble apologies for rhyming duke with puke). In terms of political hierarchy, the dukes are the highest of nobles, as they're next in line for the throne after the royal family. Originally, this title was created for the sons of the King (enabling the sons to earn their own income), hence why in many countries, dukes are considered royalty rather than nobility since only royals possess dukedoms. Following, the title was created as the highest honor of service rendered to the Crown (did you know Winston Churchill was offered a dukedom (twice!) but declined the offer (twice!)?). Traditionally, a duchy encompassed an entire county--Northumberland, Cornwall, York, etc.--but not necessarily anymore. The number of dukes is small. Currently, there are only 24 non-royal dukes, and that number will only dwindle as time passes because outside of royal dukes, no new titles will be created. The highest number of dukes that has ever existed in England was in 1727 with a grand total of 40 dukes. A duke is addressed as His/Your Grace and a duchess as Her/Your Grace, but never as My Lord/Lady. He would be the Duke of DukedomName (such as Duke of Annick) and Lord Annick (never Lord Firstname or Lord Surname or Lord First & Surname). All children, even younger sons, of a duke are styled Lord/Lady. I've shared this source before on forms of address, but I'm going to do it again because you really must bookmark it!

Duke from Debrett's

A marquess possesses a marquisate (the title and rank) and oversees a march (the physical territory of rule). (Note: it is spelled marquess. Marquis, as you might sometimes see it, is the French variation. It's also pronounced mar-kwis, not mar-key (which, again, is the French variation)). The marquess is an interesting position that is rarely ever used correctly in fiction. Am I going to misuse this position for future heroes? Of course! Originally, the marquess rank was given to either already established dukes (or those in line to inherit a dukedom) or earls who lived along the border. The rationale was to strengthen the bordering lands by stationing soldiers with a leader who would protect from border attacks from Wales or Scotland. In this way, a marquess wasn't part of the hierarchy as we know it, as it was only a lesser title granted to an existing title holder to distinguish them as a border-ruler. Thus, a marquess and his march would always be on the border and always be in line for a dukedom/earldom or already in possession of a dukedom/earldom. Over time, as with all these titles, things changed, and now we'll find marquesses who don't reside on a bordering land and who are not in line or in possession of a dukedom/earldom. Originally, though, imagine the country's layout--the marquesses oversaw the border territories while the earls oversaw the interior territories. A marquess is addressed as My Lord or His/Your Lordship and the marchioness as My Lady or Her/Your Ladyship. He would be the Marquess of MarquisateName (such as Marquess of Pickering) and Lord Pickering (never Lord Firstname or Lord Surname or Lord First & Surname). All children, even younger sons, of a marquess are styled Lord/Lady.

Coronet Detailing from Encyclopedia Britannica

An earl possesses an earldom. Earls have a longer history of existence than dukes, as they were the original title to be granted below royalty for services rendered to the Crown. They were the highest of noble titles at one time. Historically, they would have authority, court judgement, and tax collecting rights of their holdings and be the overseer of the King's army for the soldiers in the earldom. Needless to say, earls were powerful. They lived in well-fortified castles with armies and even had their own coins minted. You can see why this would make any King a wee bit nervous should his dearest friends turn enemies, thus earls were steadily stripped of their rights by nervous rulers and even had their castles destroyed (poor Dunstanburgh Castle). After a time, earls became equal (or should we say were lessened) in wealth and power to other nobles and served the primary purpose of being the supporters of the King's power and right-hand man in battle. Originally, earls ruled the counties or shires (not the dukes. An earl was a "count" who ruled a "county"), but overtime, that ruling broadened to encompass larger or even smaller holdings. An earl is addressed as My Lord or His/Your Lordship and the countess as My Lady or Her/Your Ladyship. He would be the Earl of EarldomName (such as Earl of Roddam) and Lord Roddam (never Lord Firstname or Lord Surname or Lord First & Surname). His daughter is addressed as My Lady. His eldest son will have a courtesy title and be addressed as My Lord, and his younger sons will all be Mr. Surname.

Earl from Debrett's

A viscount was originally not a hereditary title rather a rank given to a military commander or sheriff to serve as vice-count (or should we call them a visearl since count became earl? Deep thoughts...) to help earl's govern their territory. (Note: it is pronounced vy-count with a silent s, rhyming with eye-count.) As with all titles, this eventually changed to become a hereditary title with landownership. A viscount does not oversee an area as does a duke, marquess, or earl, and therefore is styled Viscount Title rather than Viscount of Place (Viscount Dunley or Lord Dunley, for instance), as there is no area to be a viscount of. If you spot a real viscount styled with of, then it is not in reference to an ownership of land but rather a distinguishing of where he lives. For instance, if we give Mr. Darcy a title, he might be Viscount Sexy of Pemberley. The of isn't a reference of place overseeing so much as a literal home name of where he's residing. Most viscount titles are secondary titles of a duke, marquess, or earl rather than a standalone (and thus styled as courtesy titles by an eldest son), but as we've said before, times change, titles change, the needs of the Crown change, and so we do have a number of standalone viscounts now who are not holding a courtesy title or in line to inherit. They are, instead, viscount of a house with a nice view. A viscount is addressed as My Lord or His/Your Lordship and the viscountess as My Lady or Her/Your Ladyship. He would be the Viscount Title and Lord Title (never Lord Firstname or Lord Surname or Lord First & Surname). All of his children, including his eldest son would be Mr./Miss Surname.

Forms of Address Cheat Sheet

A baron was a term used for men sworn to serve militarily and attend the council of the King. Such men were granted land for their service and became landlords, the tenant holdings being known as a barony. As times changed, Crown needs changed, and so forth, both landlord and even military connection faded, leaving an honorific and hereditary title wherein the baron may oversee tenants as a landowner or may not, and if there are no tenants to oversee, then he merely holds a title, no ruling of any kind. The styling, as with viscount, would be Baron Title rather than Baron of Place (Baron Collingwood or Lord Collingwood), as there is no area to be a baron of. As with the viscount, many barons are secondary titles of a duke, marquess, or earl, and so the eldest son uses it as a courtesy title, but not in all cases. A baron is addressed as My Lord or His/Your Lordship and the baroness as My Lady or Her/Your Ladyship. He would be the Baron Title or Lord Title (never Lord Firstname or Lord Surname or Lord First & Surname). All of his children, including his eldest son would be Mr./Miss Surname.

Since baronets, knights, and squires are not part of the nobility, I've omitted them from this discussion, but I will link to a previous discussion we had on what a baronet is and what function the rank serves in light of events we see occur in The Colonel and The Enchantress.

Les Grandes chroniques de France

In Reference to the Barons' War

It would be unusual for a duke, marquess, or earl to have only one title. Secondary titles typically came to be by way of inheritance from different branches of the tree (an earl inheriting a barony from a distant relation, for instance), by marriage to an heiress (marriages are political!), and by way of accolades. Accolades could happen in a few ways: (a) the same monarch awards a new title for every act of extraordinary service, (b) a new monarch awards additional accolades, such as the aging King awarding a loyal retainer with an earldom only to have the next King award the earl with another earldom for continued loyalty, (c) a monarch awards simultaneous accolades (such as the previously mentioned Winston Churchill who was offered both a knighthood and a dukedom simultaneously (twice!)), or such as the King being so pleased with a loyal retainer's service that he offers a dukedom, an earldom, and a barony to the same fellow at the same time. If we recall in The Earl and The Enchantress, our hero had 5 earldoms and 1 barony. While the Earl of Roddam is fictional, his inspired and very real ancestor the 2nd Earl of Lancaster had just that--5 earldoms and 1 barony. Regardless of number of titles, they are styled by their highest and oldest rank.

This brings us to courtesy titles. Not all peers had secondary titles. The higher the gent in the political hierarchy, the more likely he was to have secondary titles. Should he have a secondary title, his heir apparent (that is his eldest son of the direct line--primogeniture) would be styled by the highest ranking of the secondary titles (as long as that ranking is not the same as the father. For instance, an earl with 5 earldoms and 1 barony would not have an heir also styled as earl, rather the heir would be styled by the next "lesser" title, which in this example is baron; however if a duke held the secondary titles of marquess and baron, the heir would be styled marquess since it is the highest rank of the two but not equal to his father's title). The heir with the courtesy title is not a title holder, is not a peer, and does not sit on the House of Lords. It is strictly a courtesy title. An heir presumptive, that is a relative who is in line to inherit if the current peer does not produce an heir of his own, cannot carry a courtesy title. Courtesy titles are for the direct heir only.

No matter how many secondary titles the father has, only the heir apparent has the right to the courtesy title, for his younger siblings will simply be plain Mr. Surname (or in the case of a duke's or marquess' younger sons, Lord Surname--the only time you'll ever see "lord" paired with a surname). If we suppose that our beloved and grumpy hero Sebastian Lancaster, Earl of Roddam, has three sons (which he doesn't), then they would be styled as the following: Lord Embleton for the heir to reflect Sebastian's "lesser" title of Baron Embleton, Mr. Lancaster for the second son, and Mr. Lancaster for the third son. If we suppose that our dandified and musical hero Drake Mowbrah, Duke of Annick, has three sons (which he does), then being the sons of a duke, the heir would have the courtesy title and the younger sons would be styled Lord Surname: Lord Sutton for the heir to reflect Drake's "lesser" title of Marquess of Sutton, Lord Mowbrah for the second son, and Lord Mowbrah for the third son. (Again, the only time you'll ever see Lord Surname).

Francis Basset, 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Basset (1757-1835), Batoni 1778

This is a conversation for another time, (namely when I add my research for The Heir and The Enchantress) but I'll just add a quick little something on entailment. Entailment of titles is different from entails of landed gentry. The same principles apply, but there are keen differences. Titles and all rights and privileges therein do not belong to the person or family. The home is not the person's or the family's. The land is not the person's or the family's. The wealth is not the person's or the family's. The peer with the title is a title holder. That peer holds the title, home, land, wealth, etc. to the best of his abilities until the next in line comes to hold it. The title, wealth, home, land, etc. belong to the Crown, and the right to hold it is granted by the Crown to that family and its lineage. Should the Crown want it back, they can take it. The holder cannot sell it, unentail it, choose an heir that's not his eldest son by way of primogeniture, etc. He is, if you will, a sort of high ranking steward (all of the aristocracy just frowned at me for comparing them to stewards, but you get my point).

In contrast, gentry are homeowners. They can do whatever their heart desires with the land, money, and home (within reason) since they own it, even disinherit their eldest son and will it to their youngest daughter or sell it or sell pieces or rent the land, or anything. They can entail it if they want, but the entailment is more in the way of a strict settlement where they can choose which line, which heir, and which rules the property will follow, such as a fee tail female, or maybe an entail with stipulations such as if the eldest son doesn't marry by his 30th birthday, the home and land will pass to the cousin. An entailment of a homeowner can even be broken if the current owner and the heir were to agree that the heir doesn't want it (which definitely wasn't the case with Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice!). Conversely, entails related to titles cannot be broken since it is not the title holder's right to do so (such as you might have seen in Downton Abbey).

While we're talking titles, lets end with the word dowager. Generally speaking, the term refers to an aristocratic widow, or a woman whose titled husband is deceased. But it's a bit more complicated than that. The use of the word has changed in popular fiction, and I'm not actually sure why or when this change took shape. The historical usage of the word is an honorific to distinguish the widow of the previous peer from the wife of the current title holder if the current peer is a direct descendant of the previous title holder (i.e. one of his sons). In this way, the widow would need to be the mother, stepmother, or grandmother of the current peer. The widow would not be referred to as "dowager" until and unless the current title holder marries. The widow will remain Lady Title. Once the title holder marries, the widow will be styled Dowager to distinguish her from the current title holder's wife. For example: the Duchess of Annick being the wife of the current peer and the Dowager Duchess of Annick being the widow. The term would not be used without the title, as it is an honorific. So someone would not say, for instance, "I saw the dowager today." They would, instead, say, "I saw the dowager duchess today," or more properly, "I saw the Dowager Duchess of Annick today." Think of "dowager" like the word "honorable." You wouldn't say "I saw the honorable today," rather you'd say, "I saw the Honorable Marquess of Pickering today." Don't think of it as a synonym to widow rather as an honorific. If the new peer is not yet married, the widow would retain her title and not be referred to as a dowager. She would simply be Lady Annick or the Duchess of Annick until the new peer married, and even then, it's really her prerogative on the styling. For an easy summary, the word "dowager" would be added to the title (not as a standalone word) if all following conditions have been met:

-

The woman is an aristocrat.

-

The woman is a widow.

-

The new peer is in the direct line of the deceased peer (son or grandson).

-

The new peer is married.

All of this said, it has not only become common in popular fiction to use dowager as a substitute for widow, but also for widowed women regardless of their caste or position or the current peer's marital status. While not the correct usage, these versions have steadily become acceptable. Fascinating how language changes.

Maggie Smith as Violet Crawley, Dowager Countess of Grantham, Downton Abbey

Note: All research sections are here for entertainment purposes to offer insights into the research and plotting of novels. Information does not represent historically accurate scholarship, only research findings that aided in crafting fictional novels.